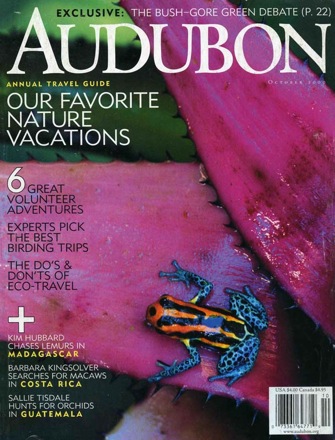

Seeing Scarlet

By Barbara Kingsolver and Steven Hopp

They’d never seen a scarlet macaw except in a cage. So this best-selling author and her ornithologist husband decided to seek the magnificent bird in one of its last strongholds: Corcovado National Park. Picture a scarlet macaw: a fierce, full meter of royal red feathers head to tail, a soldier’s rainbow-colored epaulets, a skeptic’s eye staring from a naked white face, a beak that takes no prisoners.

Now examine the background of your mental image: Probably it’s a zoo or a pet shop, with not a trace of the truth of this bird’s natural life. How does it perch or forage or speak among its kind without the demeaning mannerisms of captivity? How does it look in flight against a blue sky? Few birds that inhabit the cultural imagination of Americans-north and south-are so familiar and yet so poorly known.

As biologists who have increasingly turned our work toward the preservation of biodiversity, we are both interested in and wary of animals as symbols. If we could name the thing that kept pushing us through Costa Rica in our rented jeep, on roads unfit for tourism or good sense, it would have been, maybe, macaw expiation. Some sort of penance for a lifetime of seeing this magnificent animal robbed of its grace. We wanted to know this bird on its own terms.

As we climbed into the Talamanca Highlands on a serpentine, pitted highway, the forest veiled the view ahead but promised something, always, around the next bend. We were two days and 60 miles south of San Jose, in a land where birds live up to the extravagances of their names: purple-throated mountain gems, long-tailed silky flycatchers, scintillant hummingbirds. At dawn we’d witnessed the red-green fireworks of a resplendent quetzal as he burst form his nest cavity trailing his tail-feather streamers. But no trace of scarlet yet, save for the scarlet-thighed dacnis (Yes, just his thighs-not his feet or legs). We had navigated through an eerie morning mist in an elfin cloudforest and at noon found ourselves among apple orchards on such steep slopes they seemed flung there instead of planted. All of it was wondrous, but we’d not yet seen a footprint of the beast we’d come here tracking.

Then a bend in the road revealed a tiny adobe school, its bare-dirt yard buzzing with small, busy children. The Escuela del Sol Feliz took us by surprise in such a remote place-but in Costa Rica, where children matter more than an army, every tiny hamlet has at least a one-room school. This one had turned its charges outdoors for the day in their white-and-navy uniforms, and the schoolyard seemed to wave with neat nautical flags. The children carried tins of paint and stood on crates and boxes, painting a mural on the school’s stucco face: humpbacked but mostly four-legged cows, round green trees festooned with round red apples, fantastic jungles dangling with monkeys and sloths. In the center, oversize and unmistakable, was a scarlet macaw.

Once, it was everywhere in the lowlands at least, on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts of this country. But in recent decades Ara macao has been pushed into a handful of isolated refuges as distant as legend from the School of the Happy Sun. Its celebrity in the school’s mural cheered us, because it seemed a kind of testimonial to its importance in Costa Rica’s iconography, and to the scattered, growing efforts to teach children here to take their natural heritage to heart. We’d come in search of both things: the scarlet macaw, and some manifestation of hope for its persistence in the wild.

Our destination was Corcovado National Park, on the Osa Peninsula, where roughly 1,000 scarlet macaws constitute the most viable Central American population of this globally endangered bird. The Osa is one of two large Costa Rican peninsulas extending into the Pacific; both are biologically rich, with huge protected areas and sparse human settlements. Corcovado, about one-tenth the size of Long Island, is the richest preserve in a country known for biodiversity. Its bird count is nearly 400 species; its 140 mammals include all six species of cats and all four species of monkeys found in Central America. It has nearly twice as many tree species as the United States and Canada combined. The park was established be executive decree in 1975, but its boundaries weren’t finalized for nearly a decade, until after its hundreds of unofficial residents could be relocated. Hardest to find were the gold prospectors-who had a talent for vanishing into the forest-and the remnant feral livestock, though the latter disappeared gradually with the help of jaguars.

For us, Corcovado would be the end of a road that was growing less navigable by the minute. Our overnight destination was Bosque del Cabo, a private nature lodge at the southern tip of the peninsula, and our guidebook promised we’d cross seven small rivers to get there. We hadn’t realized we’d do it without the benefit of bridges. At the bank of the first river, we plunged in with our jeep, fingers crossed, cheered on by a farmer in rubber boots leading his mule across ahead of us.

“This will be worth it,” Steven insisted when we reached the slightly more treacherous-looking second river. No bridge in sight, no evidence that one had ever existed, through a sign advised: PUENTE EN MAL ESTANDO-bridge in bad state. Yes, indeed. The code of Costa Rican signs is a language of magnificent understatements; earlier in the trip we were informed by a sign posted on a trail up a live volcano: “Esteemed hiker, a person could sometimes be killed here by flying rocks.”

Over the river safe and sounds, with Golfo Dulce a steady blue horizon on our left, we rattled on southward through small fincas under the gaze of zebu cattle, with their worldly wattles and huge, downcast ears. Between farms the road was shaded by unmanicured woodlots, oil-palm groves, and the startling monoculture of orchard-row forests planted for pulp. Seedeaters and grassquits lined the top wires of the fences like intermittent commas in a run-on sentence.

At dusk, with seven rivers behind us, we pulled into the mile-long driveway of Bosque del Cabo under the darkening canopy of rainforest. The road tunneled between steep, muddy shoulders, but we could smell the ocean. Our headlight beam caught a crab in the road, dead center. We slid to a stop and scrambled out for a closer look at this palm-sized thing. A kid with a box of Crayolas couldn’t have done better: bright purple shell, red-orange legs, marigold-colored spots at the base of the eyestalks. We dubbed it the “resplendent scarlet-thighed crab” and nudged it out of the road. But we immediately encountered more, and suddenly we were seriously outnumbered. Barbara surrendered all dignity and walked ahead of the jeep at a crouch, waving her arms, but as crab-herd she was fighting a losing battle against a mile-long swarm. These land crabs migrate mysteriously in huge throngs between ocean and forest, and on this moonlit night they caught us in a pulsing sea of red that refused to part. They danced across the slick double track of their flattened fellows, left by drivers ahead of us. We’ve rarely traveled a longer, slower crunchier mile than that one.

We slept that night in a thatched palapa, lulled by the deep heartbeat of the Pacific surf against the cliff below us. At first light we woke to the booming exchanges of howler monkeys roaring out their ritual “Here I am!” to position their groups for a morning of foraging. We sat on our little porch watching a coatimundi poking his long snout into the pineapple patch. A group of chestnut-mandibled toucans sallied into a palm, bouncing among the fronds. No macaws, through we were in their range now. We walked out to meet this astonishing place, prepared for anything-except the troop of spider monkeys that hurled sticks from the boughs and leaped down at us using their prehensile tails in a Yankee-go-home bungee-jumping display. Retreating toward our lodge, we heard a parrotfish squawk in the treetops that we recognized from pet shops. Were they macaws?

“Si, guacamayos,” we were assured by a gardener we found shaking his head over the raided pineapple patch. Yes, he’d been seeing macaws lately, he said, usually in pairs, “Practicando a casare”-practicing to be married. This was April, the beginning of the nesting season. Following courtship rituals, the macaw pairs would settle into tree cavities, always more than 100 feet above the ground, and lay their two-egg clutches. The young stay with the adults for as long as two years; no more nesting occurs until after they have dispersed. This combination of specialized habitat and slow reproduction makes macaws especially vulnerable to an assembly of threats. The ravages of aerial pesticide spraying have lately diminished, as banana companies leave the country or switch to oil-palm production, but deforestation remains a phenomenal peril. Of the macaws’ original Costa Rican habitat, only 20 percent still stands, all of it now protected. In addition to the Osa population, some 330 birds survive in the Carara Biological Reserve, to the north; scarlet macaws are also found in scattered pockets from southern Mexico into Amazonian Brazil.

Dire habitat loss has become the norm for tropical species, but macaws and parrots are further doomed by their own charm. The price of beauty is high for a young scarlet macaw captured by a poacher, who can sell it into the pet trade for as much as $400. (The fine for being caught is about $325.) Since 1990, when the nearby town of Golfito was allowed to begin collecting lower taxes on goods that come through its port, employment from the import trade has grown and poaching has declined noticeably. Farther north, however, in the economically undeveloped Carara region, poaching is ubiquitous. Many local conservationists feel the best hope is to develop alternative sources of income while educating children about the long-term trade-offs of poaching, which could extinguish a national emblem before they’re old enough to be adept at climbing 100-foot trees. During our trip, we spoke with several educators whose programs aim specifically at developing a family conscience about stealing baby parrots and macaws from their nest holes-revising a culture in which these birds have traditionally been harvested with no more moral qualms than a hungry coatimundi brings to a pineapple patch.

El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste, the Costa Ricans say-If you want the blue sky, the price is high. The mix of hope and fatalism in this dicho speaks perfectly of the macaw’s fierce love of freedom and touching vulnerability. We stood on the cliff near our palapa above the ocean, scanning, hoping for a glimpse of scarlet that wasn’t there. Today we would complete our pilgrimage to Corcovado, where we would see them flying against the blue sky or we would not. On a trip like this, you revise your hopes: If we saw even one free bird, we decided, that would be enough. We prepared to push on the final 10 miles to the road’s end at Carate, gateway to the Corcovado forest, home to the country’s last great breeding population of scarlet macaws.

Carate, although it appears on the map, is not a town. It’s a building. Mayor Morales’s ramshackle pulperia serves the southwestern quadrant of the peninsula as the singular hub of commerce: He’ll arrange delivery-truck passage back out to Puerto Jimenez, buy gold you’ve mined, watch your vehicle while you hike, or simply offer a theoretical restroom among the trees out back. Indoors, dangling by wires from the ceiling, is a dazzling collection of bottles, driftwood, bird’s nests, car parts-the very definition of flotsam and jetsam, if you can tell what floated in and what was jettisoned. Above the main counter dangles the crown jewel of the collection: a mammalian vertebra of a size generally seen only in museums. Under this Damocles bone we purchased a soda and plotted our strategy for finding macaws. Outside, on benches under a tree, we sat among the pulperia regulars, who explained to us that there are no roads into the park, no hiking trails, no wooden signboard maps declaring that you are here. Corcovado is not the user-friendly kind of national park we’re accustomed to. How do you get in? You walk, and watch out for snakes. It’s a thick jungle; where’s the best walking? The beach.

While we chatted, a pet spider monkey sidled up to Barbara. Steven focused the camera. A barefoot girl nearby watched intently.

“Is he friendly?” Barbara asked in Spanish.

The girl grinned broadly. “Muerde.” He bites.

Steven snapped the photo we now call “interspecific primate grimace.”

The steep gray beach offered rugged access to the park. The surf pounded hard on our left as we hiked, and to our right the wall of jungle rose steeply up a rocky slope. A series of streams poured down the rocks from the jungle into the Pacific. At the forest’s edge the towering trees were branchless trunks for their lowest 100 feet or so. From this sparse, lofty canopy we began to hear macaws-not the loud, familiar croak but a low conversational grumbling among small foraging groups. We jockeyed for a view, catching glimpses of monkeylike clusters at the tips of branches. Macaws are seed predators, cracking the hearts of fruit seeds or nuts. High above the ground is where you’ll see them, only and always, if you don’t want boars for backdrop. Both the scarlet and the other Costa Rican macaw, the great green, rely on large tracts of mature trees for foraging, roosting, and nesting.

It’s hard to believe something so large and red could hide so well in foliage, backlit by the tropical sky, but they did. We squinted, wondering if this was it-the view we’d been waiting for. Suddenly a pair launched like rockets into the air. With powerful, rapid wingbeats and tail feathers splayed like fingers, they swooped into a neighboring tree and disappeared uncannily against the branches. We waited. Soon another pair, then groups of three and five, began trading places from tree to tree. Their white masks and scarlet shoulders flashed in the sun. A grand game of Musical Trees seemed to be in progress as we walked up the beach counting birds that dived between trees.

All afternoon we walked crook-necked and open-mouthed in awe. If these creatures are doomed, they don’t act that way. El que quiera azul celeste, que le cueste, but who could buy or possess such avian magnificence against the blue sky? We stopped counting at 50. We’d have settled for just one-we thought that’s what we came for-but we stayed through the change of tide and nearly till sunset because of the way they perched and foraged and spoke among themselves, without a care of a human’s expectation. What held us there was the show of pure, defiant survival: this audacious thing with feathers, this hope.